JEAN-GABRIEL GANASCIA: “TECHNICAL ACHIEVEMENT ALONE CANNOT BRING SATISFACTION”.

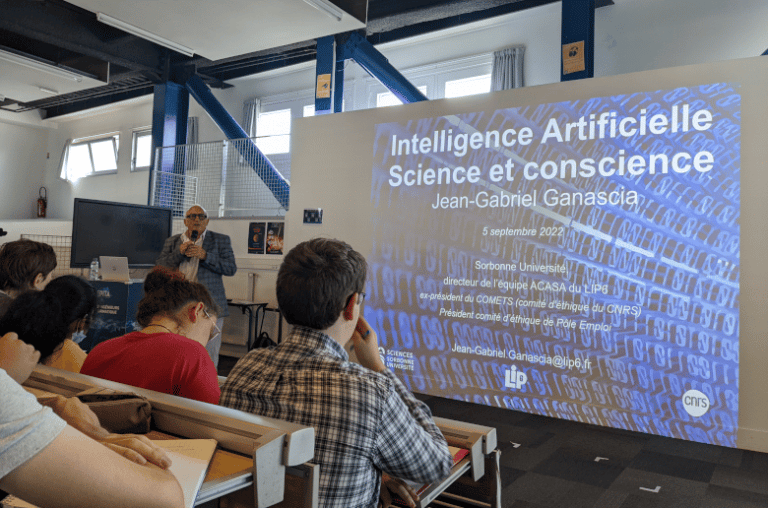

Organized from September 5 to 9 for 2nd year students, the 15th edition of EPITA’s Research & Innovation Week allows future engineers to discover a myriad of exciting fields, thanks to conferences, presentations and workshops given by numerous researchers and recognized professionals, starting with Jean-Gabriel Ganascia.

The guest of honor at this new edition is a widely recognized researcher from LIP6 (Computer Laboratory at the Sorbonne University) and recent prize winner in University Research at the FIC 2022 book award for “Servitudes virtuelles” (Seuil), Jean-Gabriel Ganascia inaugurated the week by dedicating his speech to the ethical dimension of his favorite field: artificial intelligence (AI). We can say that Rabelais’ famous quote, “Science without conscience is but the ruin of the soul,” remains more relevant than ever almost 500 years after it was written!

Why did you agree to inaugurate this Research & Innovation Week at EPITA?

Jean-Gabriel Ganascia: I thought it was a good idea to share a certain amount of information with young people who are about to embark on a career in engineering, for two reasons. The first is related to the definition of artificial intelligence, which is often quite obscure, as technical classes do not generally cover it. This was an opportunity to explain all of the dimensions of artificial intelligence, which I hope to have done in a clear manner. The second reason is that I wanted to raise the students’ awareness of ethical issues by sharing some examples of what could be done. Of course, there is not enough time to cover everything in only one lecture, but I still believe that it was important to initiate this discussion.

Does the role of a researcher include sharing and handing down knowledge?

Jean-Gabriel Ganascia: Above all, the role of a researcher is to create new knowledge. However today, this vocation also includes innovation, and the transmission of this knowledge to the socio-economic sector, so that it may be useful to all of society. In my opinion, we also need to educate the population as a whole and explain what is being done. Indeed, the past few years (following the pandemic, in particular) have shown that the general population may misunderstand or even feel hostility towards scientists. I therefore believe that it is extremely important for scientists to accept this role of transmitting information to young people and to society as a whole. This is also a political issue. As a researcher, I was outraged at seeing false information circulating. We have to explain what the scientific process is, remind people that it follows a certain number of explicit and transparent procedures, and that nothing is hidden. Of course, there can also be errors, but it is the role of the scientific community to detect and then eliminate them. And even though there may be dishonest researchers, we must be aware that the majority of those in our field work in an extremely honest manner and that the scientific community functions, not as a pressure group or a lobby, but as a community in search of knowledge and the truth.

During your lecture, you used many examples from literature and philosophy. Is it necessary to have this literary background when you wish to become an engineer or a researcher in AI?

Jean-Gabriel Ganascia: You can obviously embark on a career in engineering with a different background – not all engineers are expected to be trained as philosophers – but I believe that it is nonetheless important to have a good understanding of the references used in the research community. For example, in the United States, science fiction plays an extremely important role in the minds of businessmen: you cannot completely understand the major projects they are working on without being familiar with these imaginary and cultural backgrounds. I think it is therefore in an engineer’s interest to know them, especially as they may find these worlds fascinating because they often reflect what initially motivated them. It is therefore not an obligation, but nevertheless desirable. In fact, we cannot only be satisfied with technical realization and the fact that it works: there is also a purpose, another goal, to respond to demands, desires and help for the future, and to transform society. These changes can be for the better or for the worse, and it is precisely when one embarks on a career in engineering that it is important to know what you would like to accomplish. This is the case for EPITA students: they must analyze their activities and remember that the work they do must not only be seen as a means of paying the rent. This is all the more important today, as we live in an increasingly difficult and complex world, with considerable challenges facing the new generations. It is only through knowledge, know-how and technology that we will be able to meet these challenges head on, rather than by closing our eyes and burying our heads in the sand.

Although certain people see AI as a potential threat, you seem to be more optimistic about it. However, is there a risk that the use of this new form of intelligence may also have a negative impact on our own intelligence?

Jean-Gabriel Ganascia: It is as much a question of intelligence and communication and information techniques as it is of human language. This reminds me of the story of Aesop, a very philosophical slave from Antiquity. One day, his master is preparing to host very dear friends and asks him to create the best meal imaginable, using the best ingredients available, with no budgetary limits whatsoever. Aesop does just that. For the first course, he serves tongue. The guests are delighted. However, he also serves tongue for the main course, and then again for dessert. The guests still find that although it is absolutely delicious, the meal lacks variety. Aesop then explains that nothing could be better than tongue, because it is thanks to this that people come together and create great things. Everyone begins to laugh, so the master asks him to prepare the worst meal imaginable, When the master’s friends return two weeks later, Aesop again serves tongue at every course of the meal! They ask him if he is taking them for fools and he answers that although there is nothing better than tongue, there is also nothing worse than tongue, as it is the source of slander, discord, wars, etc.

This is the same with digital technology and artificial intelligence. They allow us to accomplish amazing things in the field of health, workflow automation, with extraordinary calculations and a form of drudgery that disappears, even with automatic translation that allows us to reduce barriers between men… Yet at the same time, they can also have detrimental effects on society, in particular on the destruction of the social fabric and the multiple political changes caused by digital technology… From a cognitive point of view, this is also the case. Let’s look at the Internet: it has made the extraordinary dream of living one’s entire life, night and day, in a library a reality, which never existed before in the history of mankind. But behind this progress, there are also certain tasks that we no longer or rarely do. We use fewer mental calculations, become less patient, read less and less from one end to the other – horizontal reading is replacing linear reading -, etc. This can have negative consequences. Thus, our role as educators is to train the younger generations to make the most of these technologies, while avoiding the pitfalls. The Internet allows you to obtain information about all subjects, it’s true, but it can also leave you a victim of rumors, false information, intellectual isolation… You have to be aware of this.

At the end of my book “Servitudes virtuelles”, I use an example that I find very touching. It’s the story of a young journalist who, in 1939, when the war was declared, tries to launch a rag – a double-sided page – when he doesn’t have any paper left. In these difficult conditions, he asks himself what a journalist’s ethics should be. For him, it is to, above all, be extremely vigilant and lucid, which is still true today: one must be lucid about information. Then there is refusal: the refusal to broadcast anything and everything, to compromise oneself. Then there is irony, which is essential in getting around all types of censorship. Finally, there is persistence. Although the situation today is completely different from the past, between the shortage of paper and censorship then, and the proliferation of publications now, I believe that these four watchwords remain extremely important and that they perfectly define the ethics of information. This young man, who was 26 years old at the time, would later become famous, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature: Albert Camus!

Finally, in addition to your own work, would you have another book to recommend to the younger generation?

Jean-Gabriel Ganascia: That is a difficult question… If we return to the theme of science fiction, I would suggest taking the time to read – or reread – “Rossum’s Universal Robots,” the play written in 1920 by Karel Čapek that gave birth to the word “robot” (rob meaning “slave” in Slavic). Even though this play is not extraordinary, and we can find much older traces of automatons in literature, such as in Homer, it is interesting to see that the developed themes echo those of today, even though society has undergone significant technological changes since the beginning of the 20th century. It is important to understand that anxieties have been embedded in the heart of mankind for centuries and that change, although fascinating, can also prove to be worrying: it is often during periods of great change that cataclysms occur, with attempts to withdraw, the resurgence of old ways of thinking, a return to obscurantism… And this is what must be avoided at all costs.